top of page

Designing control systems to teleoperate the first private, student built lunar robot.

2018-2019

Carnegie Mellon University

Roles & Responsibilities

UX Design

Mission Ops Design

Research

Key Collaborators

Alessandra Fleck, Annette Hong, John-Walker Moosbrugger, Antonio Song, Nina Yang

Problem

How can we navigate on the moon with limited visibility and knowledge of the terrain?

Background

Upon successful deployment on the Moon, Iris Lunar Rover (The Robot Formerly Known as CubeRover) will be making history as the first university built rover and first American lunar robot on the Moon. Iris weighs 2kg and is the size of a shoebox.

When the teleoperations team formed in the fall of 2018, our first task was to define the roles and responsibilties for the mission control team. As we added more designers in spring of 2019, I began to define the image viewer and command line interfaces.

Constraints

Iris will be teleoperated from a command center on Earth, with an 11 second time delay between commands and limited bandwidth for data coming back. The robot has a limited field of visibility and only 2 cameras, one on the front and one at the rear.

Integration, launch, transit, landing and deployment will be handled by Astrobotic. Once on the moon, the teleoperations team takes control and Iris can start to explore the lunar surface and conduct its science mission.

Solution

Defined flight rules, communication and decision making strategies, and an MVP user interface to control the robot which consisted of a telemetry view, a command line, a shared map, and an image viewer.

Process

The process evolved through different phases of the project, but we roughly followed the double diamond design process.

Discover

We started by asking some key questions:

WHO

-

Is making decisions about where to go next?

-

Is sending the commands to the robot?

-

Is tracking the robot’s telemetry?

WHAT

-

Data to we get from the robot?

-

Commands need to be sent to successfully navigate?

-

Information about the robot’s health is needed to make decisions?

HOW

-

Do past, present, and incoming data impact the decision making?

-

Do decisions get communicated between experts in each area?

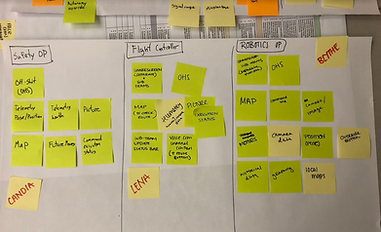

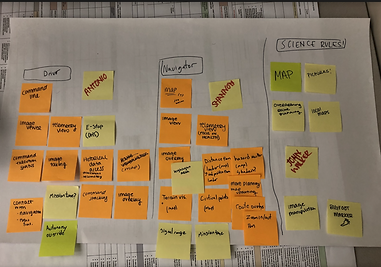

We tested some core roles needed in the control room:

-

Driver

-

Navigator

-

Science Operator

-

Safety Operator

-

Fight Controller

-

Robotics Operator

We made a first pass at what data each person would need to make decisions in their role.

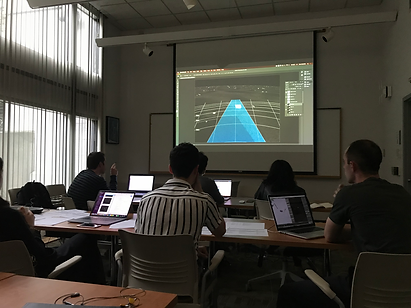

Once we had these sketched out, we began running “paper missions” where we simulated driving the robot with these roles and data inputs to refine the structure of the mission control team.

Once we had these sketched out, we began running “paper missions” where we simulated driving the robot with these roles and data inputs to refine the structure of the mission control team.

Once we had these sketched out, we began running “paper missions” where we simulated driving the robot with these roles and data inputs to refine the structure of the mission control team.

We also conducted a literature review on teleoperation of planetary robotics and the whole team read Janet Vertesi’s “Seeing Like a Rover” to understand best practices.

Define

We started by developing team communication and decision making strategies as well as creating flight rules to manage responsibilities for each member of the team.

We needed to structure a team protocol for completing our science missions from pre-deployment to execution of the operation.

After defining the general mission flow, we created a communications diagram that visualizes the flow of information between our operators during the mission.

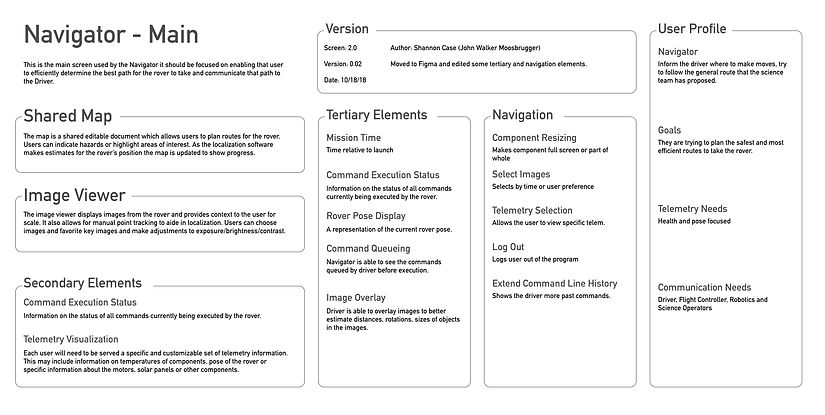

We then were able to define text based wireframes for role based on what they each needed in their interface, with the goal of designing a flexible system that could be used to drop in different modules for each function.

Develop

After defining the elements needed by each of our users, we broke into smaller teams to tackle designing the elements as modules that could be slotted in for use by different operators.

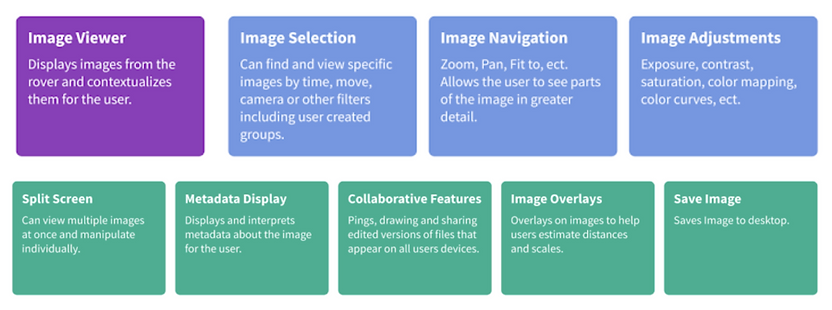

I was responsible for the design of the image viewer. I began by broadly exploring how we might go about creating an efficient interface that would meet the needs of the driver, navigator, and science officer for each of their different objectives.

I had to keep in mind that Iris is capable of capturing and transmitting images of varying sizes and compressions, and is also capable of cropping images to specific regions, which allows operators to observe far away features in high resolution without the need to transmit a full resolution image.

As a team, we'd defined a MVP for the interface, which I then broke down into the key elements and actions needed for the image viewer itself. I began by sketching on paper different elements and ideas for how they might interact.

Early on, the team was considering augmenting the visual SLAM with a human interface that would provide more accurate data points for the point tracking algorithm. The user would choose a point in one image, and try to match it to the same point in the next image.

I needed to account for the ability to zoom, pan, and select points in split screen view. The user would also need to be able to lock points in to confirm a match, toggle on & off previous points, and view the original SLAM calculation. The UI also needed to allow the user to track "features", such as rocks, which needed to be exported to the shared map and shared with the science team as potential points of interest.

After a few iterations on these interactions, we ended up scrapping the idea of augmenting SLAM and narrowed the scope of the split screen view to focus on the tagging of specific features and scientific points of interest shared across images.

In January 2019, two more designers joined the team and we broke down the work on the image viewer between the three of us.

At this point, we began to collaborate with the front-end engineers and the systems lead to begin development of an MVP interface that would be put through further testing.

Once we had a thorough understanding of the interface needed, we bumped up to high fidelity prototypes and shared in expert design reviews with faculty from the School of Design.

These are some of the higher fidelity wireframes we created for viewing and tagging features in the images.

Through this process, the team continually ran paper missions on our wireframes to test the designs and drive the robot in a simulated environment.

Deliver

In summer 2019, when I left the project, we were midway through development of the MVP interface for Iris. The final process for operating the rover during the mission is still in progress and builds upon the UI developed for this phase.

Render by Alessandra Fleck

Iris Lunar Rover is tentatively set to launch sometime 2022 on the Astrobotic Peregrine Lander’s Flagship mission onboard the first ULA Vulcan launch. The project has been contributed to by many students along the way, whose names are shown here etched onto the back of the flight computer.

bottom of page